by Ryan Bell

In India, the arrival of summer monsoons used to correlate with an upsurge in the number of people contracting polio. The heavy rains would cause sewage systems to overflow, tainting supplies of drinking water with polio-contaminated fecal material.

“It was like we were at war with an invisible enemy,” says Dr. Bhupendra Tripathi, a veteran of India’s campaign to eradicate polio. “After the rains, there were so many polio cases that infectious disease hospitals had to create polio wards for treating affected children.”

This summer, when the monsoons arrive, the people of India can rest assured their drinking water won’t be contaminated with poliovirus. Five years ago, on March 27, 2014, the World Health Organization’s 11-nation region of southeast Asia was certified polio-free, having gone three years without a documented case of the wild poliovirus. For India, a nation that once accounted for the majority of all polio cases worldwide, the eradication of polio amounts to one of the great success stories in the history of global health.

India’s success at overcoming its longshot odds of ending polio gives hope that the campaigns underway in the last three polio-endemic nations in the world—Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Nigeria—can be successful. Nigeria is just a few months away from reaching three years since its last case of wild polio (recorded on September 27, 2016). After that, the entire continent of Africa could be certified polio-free.

This summer, though, Nigeria’s efforts to end polio will be tested with one more rainy season. Statistically, a flare up is unlikely. But the memory is still fresh of when, in 2016, the nation was about to celebrate two years without a case of wild poliovirus when a surprise outbreak caught health officials off guard.

“It taught us that our surveillance and immunization efforts weren’t good enough,” says Michel Zaffran, director of polio eradication at the World Health Organization (WHO). “The outbreak was in the state of Borno, in a part of Nigeria under the control of Boko Haram. At the time, we estimate around 650,000 children went without immunization in the region, allowing the wild virus to circulate.”

In Afghanistan and Pakistan, seasonal rains have combined with political instability to propagate the wild poliovirus. In 2018, there were 33 cases in the two countries, nearly a dozen more than in 2017. This year hasn’t started much better, with two cases already reported in Afghanistan and four in Pakistan.

“The slight rise in global case counts of wild poliovirus from 2017 to 2018, while disappointing, doesn’t indicate a major change in program progress,” says Jay Wenger, who leads the polio eradication effort at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. “The numbers of cases now are so small that minor fluctuations do not tell us very much. We are very close to zero now, and what is critical is that we stop transmission. I remain confident that we are seeing continued progress toward zero, that we will soon see a world where no children will ever have to worry again about being affected by this terrible disease.”

Still, there is a growing sense of fatigue surrounding the eradication effort.

“Of course, there is a lot of frustration and disappointment that we have not finished the job of eradicating the wild poliovirus,” Zaffran says. “But look at what has been achieved. Type 2 wild polio has not been seen since 1999, so it has been declared officially eradicated. Type 3 was last seen over six years ago, in November 2012, so we believe it also has been eradicated. And we are gaining access to previously unreachable children in high-risk areas of Nigeria, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.”

This summer, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI)–a partnership between the WHO, Rotary International, UNICEF, the CDC, and the Gates Foundation–will launch a global strategy for finishing off polio by the year 2023. It draws on the wisdom earned during the India campaign, and the sobering lessons from Nigeria, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

The strategy doesn’t represent a “magic bullet,” Zaffran says. But it will “improve and intensify” the GPEI’s core strategies, adding a few innovative program features. To better detect the virus, the GPEI will intensify active surveillance for acute flaccid paralysis in children ages 15 and under. And environmental surveillance programs will start testing sewage systems not just in the endemic nations but in their neighboring countries as well.

“We don’t want to have any blind spots,” Zaffran says.

The strategy also includes a new regional emergency operation center in Amman, Jordan. From that hub, GPEI and its partners will launch their regional work, allowing for greater data analysis capabilities and larger staffing, as well as being nimble and responsive in their support of eradication efforts in Africa and the Middle East.

One of the plan’s boldest steps is to take an integrated approach to working at the community level.

“In the grand scheme of things,” Zaffran says, “33 cases of polio doesn’t feel like a big problem at the local level. Especially when people are dealing with bigger problems like unsafe drinking water, poor sanitation, malnutrition, and other vaccine-preventable diseases, such as measles. Polio vaccination will become part of a coherent package to also address the more visible needs of a community.”

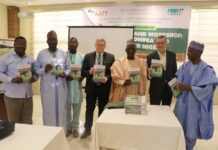

photo: Christine McNab, UN Foundation

RELATED: Keeping vaccination goals close, no matter how afar

While the GPEI’s new strategy is being finalized, India is in the midst of its own health campaign that uses the polio eradication playbook to take on a new health challenge, a neglected tropical disease called lymphatic filariasis (LF).

When polio was eliminated in India, it left people like Dr. Tripathi in search of new work. He’d been on the WHO’s polio eradication team. In 2014, he became a program officer for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. At the time, few health experts knew about the growing problem of LF transmission in India. In 2016, Tripathi learned about it while visiting a field study for a project called the “LF Mass Drug Administration Campaign.”

“I realized their program was being run similarly to the polio campaigns,” Tripathi says. “There was a lot of potential, but also a lot of learning left to incorporate from the fight against polio.”

When the Gates Foundation started contributing funding to the project, Tripathi started creating a working plan for rolling out a nationwide program using triple-drug therapy to eliminate LF. He drew on his experience from polio to build the campaign’s framework.

His first step was to create partnerships in the global health community. Tripathi helped coordinate agreements with a half-dozen organizations, such as the WHO and PATH, which provide help with everything from program planning, to drug delivery support, to social mobilization.

At the programmatic level, Tripathi worked with India’s National Vector Borne Disease Control Program to create a strategic command hierarchy that identified who had ownership of the LF campaign at the local, district, state, and national levels.

Then, he helped leverage the use of health workers with experience from the polio years to deliver the new LF treatments. Knowing that managing a multiple-drug treatment can easily get confusing, they implemented the same finger-marking system as had worked for distinguishing between people vaccinated for polio.

In a short period of time, India’s national campaign to eliminate LF took shape. All thanks to people originally trained in the fight against polio.

“As a health worker,” Tripathi says, “when you go into a community to administer drugs and vaccines, people will trust you more if they know you worked on the campaign to eradicate polio.”